At present, the world is at a critical juncture in the accelerated transition toward clean and low-carbon energy systems. In this global transformation, lithium-ion batteries play a dominant role. Although China has become the world’s largest producer and user of lithium-ion batteries, it now faces a significant challenge: mainstream lithium-ion battery technologies are approaching their theoretical energy density limits, while next-generation batteries have yet to achieve large-scale commercial deployment. As a result, further breakthroughs in endurance performance are increasingly difficult to realize—not only for everyday consumer electronics such as smartphones, but also for key emerging applications including drones and electric vehicles.

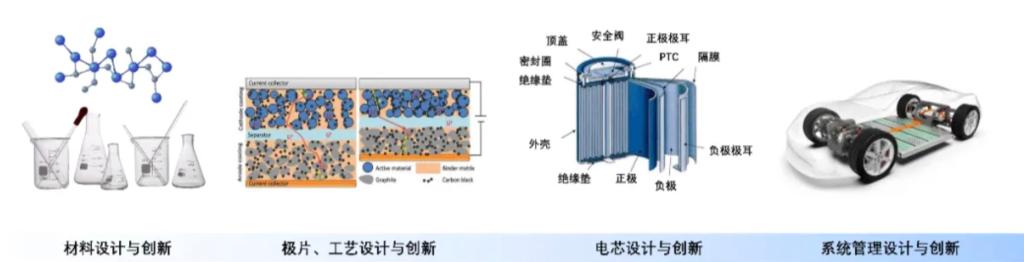

Figure 1. New Energy as a Core Competitive Advantage of China’s High-Tech Industries

“To achieve real breakthroughs, we must break away from the limitations of traditional R&D models.” Prof. Jiaxin Zheng, Associate Professor at the School of Advanced Materials (SAM) and the School of Intelligence Science and Technology, Peking University, and Founder of Shenzhen EACOMP Technology Co., Ltd., has proposed a new path forward. His research team has pioneered the development of BDA (Battery Design Automation) software, which virtualizes the traditionally complex battery R&D process. With this technology, experimental workflows that once required months—or even years—can now be compressed into simulation-based predictions completed within just a few days on a computer. This shift from experiment-driven to simulation-driven research is accelerating the transition of safer and longer-lasting next-generation batteries from the laboratory into everyday life.

Figure 2. Application Scenarios of the BDA Software

Why has the development of new battery technologies been so challenging in the past?

What limitations and bottlenecks do the traditional R&D paradigm face?

And how can these challenges be overcome?

Let us explore the answers with Prof. Jiaxin Zheng.

The Challenge: Trial-and-Error Experimentation and the “Three Major Bottlenecks”

“In the past, battery R&D relied largely on trial and error and, to a great extent, on the personal experience of senior experts,” noted Prof. Jiaxin Zheng. “It was much like preparing traditional Chinese herbal medicine or brewing liquor—master craftsmen’s experience played a decisive role.”

In the lithium battery industry, this so-called “handcrafted” R&D paradigm depends heavily on extensive experimental trial and error. Such an approach is not only resource-intensive and time-consuming, but also difficult to replicate or pass on, as expert experience is often tacit and non-transferable. More critically, conventional methods are now approaching the performance ceiling of existing battery technologies, making it increasingly difficult to achieve breakthroughs in energy density and safety. These limitations have become major obstacles for many emerging industries. For example, in the low-altitude economy, drone batteries often provide less than one hour of flight time before requiring return. A more powerful and longer-lasting battery could be the key to unlocking the full market potential of this sector.

Figure 3. Prof. Jiaxin Zheng

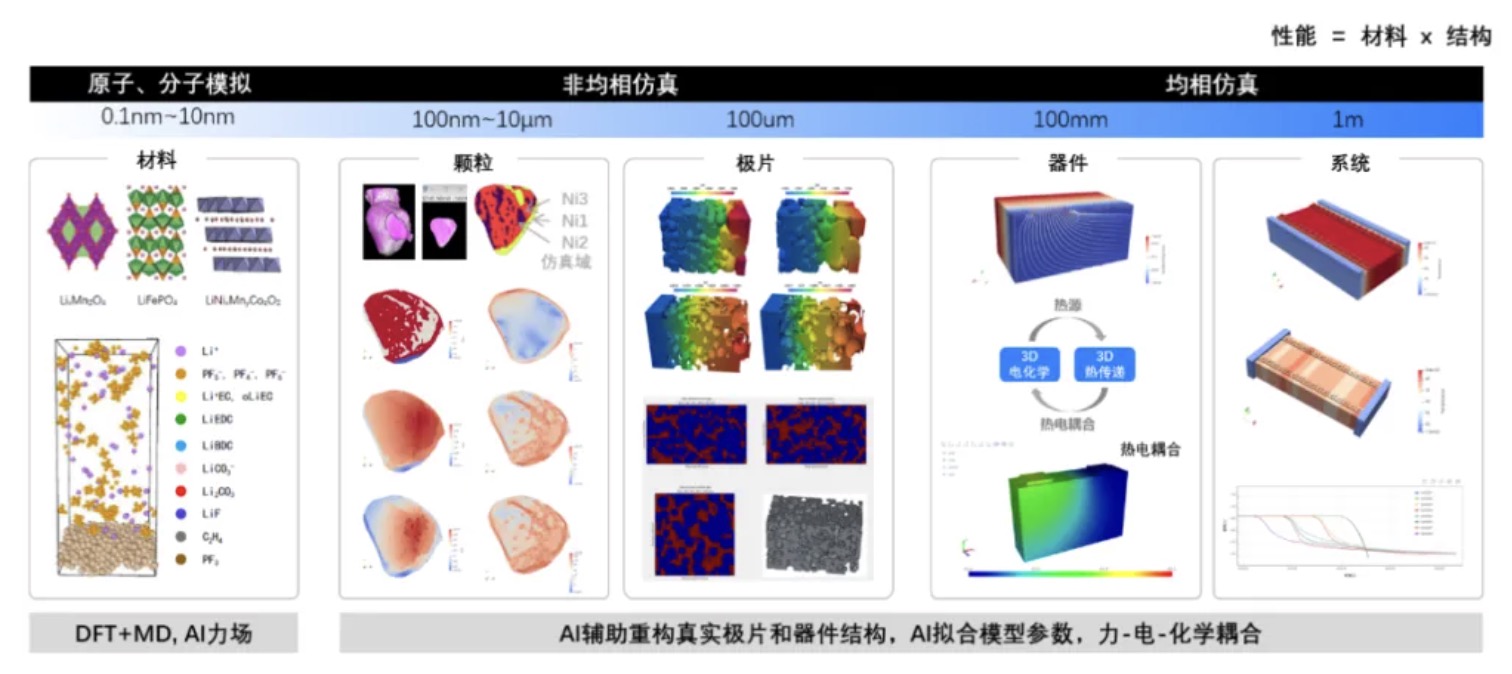

According to Prof. Jiaxin Zheng, lithium battery R&D is constrained by three inherent and formidable challenges. The first is the “cross-scale” challenge. Battery research must address phenomena across vastly different scales—from atoms and molecules at the microscopic level to full battery cells and modules at the macroscopic level—resulting in enormous gaps in both time and spatial dimensions. The second challenge lies in the “long development chain”, which begins as early as raw material extraction. Battery R&D spans the entire process from material design to large-scale manufacturing, involving production and process cycles that can last for months or even years. The third challenge is “multi-factor coupling”. Every stage of battery mass production is influenced by multiple interdependent factors, leading to complex and often elusive failure mechanisms. In such a lengthy and intricate process, different variables are tightly interconnected: a lack of control over even a single factor at one stage can ultimately compromise overall battery performance.

Figure 4. Battery R&D Challenges: Cross-Scale, Long Development Cycles, and Multi-Factor Coupling. Copyright © 2022 Wiley Ltd.

Breaking the Bottleneck: Prior Simulation and AI-Driven Innovation

How can these three major challenges be overcome? Drawing inspiration from the successful application of Electronic Design Automation (EDA) software in the semiconductor industry, and building on recent breakthroughs in AI for Science within the battery field, Prof. Jiaxin Zheng’s team has pioneered a new paradigm—BDA.

Figure 5. BDA: Dramatically Accelerating Battery R&D through Computation

At its core, BDA represents a fundamental shift in battery research—from reliance on the “hands of master craftsmen” to the “brains of computers.” This highly efficient and cost-effective paradigm allows researchers to design batteries without extensive laboratory trial and error. Instead of constantly running experiments, scientists can now work from their offices, using computers and simulation tools to explore battery designs.

By virtualizing the R&D process, BDA compresses experimental cycles that once took months—or even years—into simulation-based predictions completed within just a few days, leading to a substantial increase in research efficiency. Prof. Jiaxin Zheng illustrated this vividly: “If Thomas Edison had access to computer simulation, imagine how many filament experiments he could have saved.”

Figure 6. BDA: Data-Driven AI for Science (AI4S) and Physics-Driven Science for AI (S4AI)

Of course, no matter how advanced the design software is, batteries must ultimately be manufactured in real factories. This new paradigm—designing batteries in offices rather than laboratories—places higher demands on existing production equipment and manufacturing processes. Just as the success of chip design software has gone hand in hand with advanced and standardized fabrication facilities, the future of BDA follows the same logic. Design software and manufacturing equipment are both integral components of the new energy ecosystem, mutually reinforcing and evolving together.

However, there is a fundamental difference between batteries and chips. The operating principles of chips are governed by purely physical processes, making them a well-defined and interpretable “white box.” Batteries, by contrast, are far more complex. In addition to electronic transport governed by physics, batteries continuously involve ionic transport and intricate chemical reactions. This deep coupling of physics and chemistry gives rise to many “black box” problems that cannot be fully explained by first-principles models alone—precisely the type of challenge at which artificial intelligence excels.

To make this concept more intuitive, Prof. Jiaxin Zheng likens battery development to an integration of Western and traditional Chinese medicine. When treating illness, Western medicine typically relies on blood tests and imaging to pinpoint a specific cause. Yet for complex conditions driven by multiple interacting factors, traditional Chinese medicine does not focus solely on pathogens; instead, it incorporates experiential judgment—considering factors such as stress levels, diet, and overall lifestyle—to reach a holistic diagnosis.

In this analogy, physics-based simulation resembles Western medicine: rigorous and scientific, grounded in clearly defined physical models that trace problems back to their origins, but with inherent limitations when confronted with highly coupled, multi-factor systems. AI, by contrast, functions like traditional Chinese medicine—leveraging large volumes of data and accumulated experience to identify patterns and address “black box” problems. What BDA achieves, therefore, is the integration of both approaches. It applies physics-based simulation to aspects that can be clearly modeled, while using AI to tackle complex, data-driven challenges that defy conventional analytical methods.

Figure 7. AI-Enabled Precise Simulation Across Scales and Multi-Physics Coupling

Through deep learning algorithms, BDA is able to analyze massive volumes of experimental data and uncover complex relationships between material properties and battery lifetime that are difficult to capture using traditional methods. This enables more accurate prediction and optimization of battery performance.

The emergence of BDA as a new paradigm marks China’s leading position in the global lithium battery industry in establishing an R&D frontier centered on the integration of AI and physics-based simulation. For the industry, this approach dramatically shortens development cycles and reduces the cost of trial and error. For society at large, such next-generation productivity tools will ultimately translate into tangible public benefits. In practical terms, this means better batteries reaching consumers more quickly—longer standby times for smartphones, safer electric vehicles with extended driving ranges, and charging speeds that may one day rival the convenience of refueling a gasoline car.

Scaling New Heights: Rooted in BDA, Advancing Toward XDA

As a driving force behind this transformation, Prof. Jiaxin Zheng embodies a strong “Peking University gene,” with interdisciplinarity as its most distinctive hallmark.

This interdisciplinary imprint runs throughout his academic journey. In 2004, Zheng enrolled in the School of Physics at Peking University, while simultaneously pursuing a dual degree in Mathematics and Applied Mathematics. In 2008, he continued his studies at the Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, Peking University, to pursue a doctoral degree. “My academic path has always been deeply interdisciplinary,” Zheng remarked with a smile. This interdisciplinarity extends beyond the natural sciences to the humanities. During his time at Peking University, he developed a strong interest in liberal arts, frequently attending courses offered by the departments of Chinese language and literature, philosophy, and even religious studies. This way of cross-disciplinary thinking enabled him to keenly identify the core pain point of the new energy industry while engaging deeply in industry–academia–research collaboration: cost reduction and efficiency improvement would become the defining challenge as emerging sectors scale up. Motivated by this insight, Zheng decided to found a company to translate scientific research into industrial applications.

The company was named EACOMP, a phonetic adaptation of its English name EasyComputation, while also drawing from traditional Chinese culture. In the I Ching, “Gen” (艮) represents a mountain. Behind this name lies a profound sense of responsibility. In the face of “chokepoint” challenges in core industrial software, EACOMP aspires—guided by the idealism of Peking University—to become a “Mount Everest” in China’s foundational software landscape: standing tall on the global stage and contributing meaningfully to the nation’s scientific and technological advancement.

Figure 8. The Vision of EACOMP Technology Co., Ltd.

But how does one climb such a “Mount Everest”? EACOMP’s answer is focus. Prof. Jiaxin Zheng firmly believes that a company must first build strength before pursuing scale. BDA represents a milestone rather than the final destination. Only by establishing deep roots—by mastering a set of core competencies in a clearly defined direction—can an enterprise truly grow, expand, and flourish. Chasing trends blindly is not an option; what is required instead is discipline, patience, and sustained concentration. Expanding before becoming strong, without a genuine competitive moat, leads only to superficial growth.

Guided by this philosophy, BDA is the deep “root” that EACOMP has planted—the foundation and stronghold of its long-term development.

Looking ahead, EACOMP plans to extend BDA beyond batteries into a broader range of advanced materials industries, including display technologies, semiconductors, rubber, and plastics, ultimately evolving from BDA toward “XDA (Cross-Industry Design Automation)”. As BDA technologies are more widely adopted, consumers can expect more affordable and durable battery products, significantly longer smartphone standby times, and electric vehicles with driving ranges that surpass current limits—bringing greater convenience and new possibilities to everyday life.

Figure 9. From BDA to XDA